Interesting applications of wearables in sports: Wearables for performance atheletes

Winning at the Olympics is often not just a matter of seconds, but sometimes fractions of a second. With such intensity, equipment is vital to keeping an edge on the competition.

Aside from the engineering that goes into the garments and gear that athletes demand, a suite of sensors and technical devices previously unimaginable now cut the edge. What is that? Wearables.

In speed skating, getting low is the edge. Samsung’s Smartsuit provides 5 sensors on the lower body which track vital body positions. That data is transmitted to the coach who sees a virtual representation for optimizing position.

The coach then sends messages to nudge the skater to the correct form – for winning. Top skaters worldwide use the suit to improve their performance. What was once intuition is now science.

“Training with the Samsung SmartSuit and the immediate feedback via the smartphone can make the difference between silver and gold, ” says Jeroen Otter, national team manager for the Netherlands’ short track skating team. [1]

This is the world of wearables

Basically, wearables are technology to measure activity by some means of wearing it on the body. The earliest sports wearable was possibly the pedometer, a device worn singularly to count steps. Worn on the wrist, pressing a button told you how many steps taken in a given period.

Sports wearables today are most commonly known as the Fitbit or iWatch for capturing workout data. The iWatch tells you more than the time, and wearables aren’t just wristband mediums. The prevalence and low entry cost (<$75) of wristband wearable technology though demonstrate the nascent entry of technology from the keyboard to personal experience.

Wearables are also increasing in capability and diversifying in their application.

Wearables are woven into fabrics, built into the gear, attach to other body parts, and are worn on the skin. They can even attach to under the skin. Wearables are headsets or eyewear (think Google glass), gloves and clothes.

The technology continues to develop as well. Wearables are a combination of Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, telemetry, and Big Data analytics that provide real-time feedback as well as gross accumulation of data for analysis.

Wearables are both active and passive. Like taking a picture, the wearable can actively, measure specific events, such as running times, rates, distances, efficiency. Passively, the wearable can be “always on” to record your rest and active periods, heart rates, body temperature to name but a few.

Robust growth

The International Data Corporation’s (IDC) Worldwide Quarterly Wearable Device Tracker report predicted 125.5 million wearable devices would be shipped in 2017, up from 104.3 million in 2016. They also forecast that total will double to 240.1 million in 2021.[2]

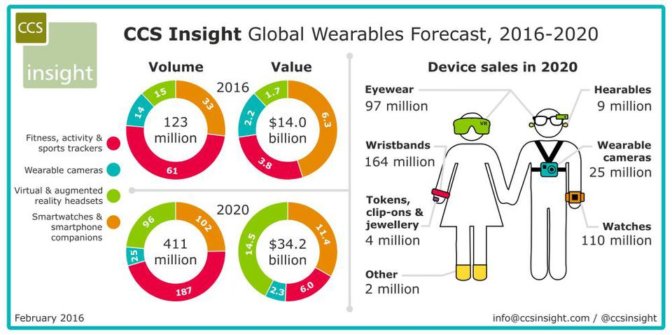

CCS Insight forecasts that all of 411 million smart wearable devices, worth a staggering $34 billion, will be sold in 2020.

Image courtesy of CCS Insight

Wearables startups revolutionising sports

So let’s take a look at a couple of the startups that are carving a sports niche out of wearable technology. We’ll start with two companies with the same concept: Sensors + Big Data + AI = better performance.

French startup PIQ raised $5.5 million in a Series A round in 2015. Consumers buy a sport-specific sensor and nanocomputer package that uses AI to analyze and interpret form to improve performance.

This applies to golf, skiing, kiteboarding, tennis and boxing. And there’s an app of course for portability and sharing.

Silicon Valley competitor Zepp has a similar approach to similar sports – baseball, golf, tennis and soccer. This startup though has raised $20 million, with the most recent $15 million Series B in 2014.

More players

The wearable sports market is completing the initial phase of awareness. The products are becoming prevalent enough that mainstream consumers are partaking as the top athletes are breaking records with R&D prototypes. Here are some examples of products in play.

Shirts

Athos has developed workout clothes – a compression fit long sleeve top and shorts – to monitor muscle activity. This is a step up from the standard suite of heart rate and respiration. The gear starts at $198 plus the reusable core at $199 – not a cheap outfit.

OM has a shirt and monitor combination. The shirt ($110-130) senses, which comes in a long or short sleeve or no sleeve. The data module ($100) collects and sends the information wirelessly. It also comes with a biometric fitness test to analyze your current ability.

Shoes

Shoes and socks may never be the same. Just as Chuck Taylor’s were made for basketball, not fashion, these products are using shoes in a new perspective – Big Data sensors. Shoes and socks can provide an infinite stream of information about our daily activities and provide feedback for our own interpretation or someone else’s.

Runsafer shoes are for runners who might be a little lonely and/or would like feedback on their running performance with notifications of fatigue or poor foot placement.

Would be good to break a plateau or prevent the hamstring pull.

The RunsaferProject involves the development of a new running shoe with embedded electronics providing real-time biomechanical feedback to reduce injury risk and enhance motivation, and a web portal allowing real training management.

Toe warmers

Another biofeedback insole, Digitsole has the added benefit of warming your toes (and feet). The product isn’t designed for it, but I’d like it to keep my ski boots warm (because the chem pads don’t work so well for me). I’d like it even more if it would analyze my skiing and snowboarding, which has a lot of room for improvement.

Back to the Olympics

Wearables aren’t only about performance improvement either. Another wearable favourite at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics was the motorbike clothing manufacturer Dainese’ creation of an upper body armour for fall protection. D-air ski inflates like an automobile airbag when certain dynamic parameters are met.

The D-air Ski algorithm deploys the system in all cases where the skier’s body performs twists which go beyond what would be considered normal race dynamics, for example forward, rear or lateral rotations during a jump or rolling over on the piste.

The algorithm only inflates the system when signals received from seven sensors exceed a preset threshold. For example, in the event of a low-speed slide not followed by rolling, the algorithm can decide not to inflate the airbag.

It’s one thing to fight for gold over silver. It’s much more important as British snowboarder Aimee Fuller said, to be “lucky to be in one piece”.

Image credit: www.istockhphoto.com